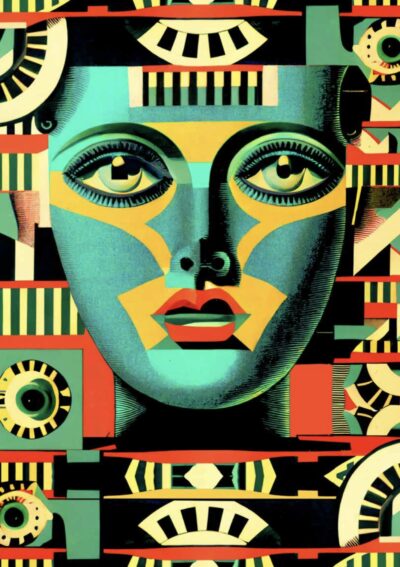

There’s a feeling when you see a stranger who resembles someone you once knew, of being thrown off kilter, caught between two people, one present before you and the other present only in your memory. I had such an experience in the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, looking at a painting by Malinowski, of Masha Zrabl. I had never met this woman – the painting is dated 1918-9 – but I felt that I knew someone like her.

Later, while studying one of the recumbent sculptures outside, I remembered. In fact it wasn’t someone else, but Masha Zrabl herself whom I knew. I had never met her but knew the outline of her life, from an old colleague, Irving Samuelson. Irving had occupied a carrel next to mine in Bristol, and later wrote an article on Masha’s work which appeared in Leonardo – an article I bothered to track down only this month, and more from loyalty to Irving (who died a few years ago now) than from an interest in Masha.

Irving’s fascination with Masha originated in his work on post-war sculpture, but blossomed after he became convinced that she appears in a story by that Hungarian author of erotic encounter, Krudy. Irving knew that Masha had two notable qualities, a pathological fear of dogs, and a hatred of Hungarians (probably a result of her birth in south Bohemia during the late Austro-Hungarian empire), and both qualities appeared in the Krudy story.

After making this possible connection, Irving sought out more information on Masha. He learned that her father died in the First World War. She and her mother were subsequently ejected from the family home – actually a castle – on the banks of the River Vltava, and she then found her way – aged nineteen – to Prague, where she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, and met her husband, a Czech poet.

Together they travelled to Paris, where they stayed in the Royal Versailles, which is the same hotel where Nabokov met Shishkov, and it is from that time that the painting in the Sainsbury Centre dates. At roughly that time, too, her husband abandoned her, and hers would have been one of those dispiriting stories of discarded muses if it were not for her meeting with the sculptor Zadkine, who admired her sculptures and asked her to join his atelier.

This is where her story truly starts, because it was while working in Zadkine’s studio that she began her improbable abstractions, from which she never wavered during her long career, carving directly from the stone without use of a maquette to model her work, a method not generally adopted – so Irving told me – until two decades later. Her work received some recognition in the late Forties, when abstraction became the prevalent mode, but then interest waned. Her death in 1989 in La Pitié Salpêtrière on the Seine, was almost solitary. Irving, who had become obsessed with her by then, visited, and said only of her that she stank and was unable to make any sense. A young man was also present in her hospital room, he said. He sat on the floor under the window, playing Donkey Kong on his Nintendo.

Irving visited her apartment building several times during her illness. She worked entirely in limestone, and in the courtyard were several of her sculptures, dissolving slowly in the polluted air and rain of Paris. Against them were propped several bicycles and, on warm days, a black dog lay across them, he said.

I have sometimes wondered whether Irving’s interest bordered on love. Certainly, if it was not for his article, Masha Zrabl would have been entirely forgotten. Her husband is still remembered in some of the anthologies of twentieth-century Czech poetry; yet Masha was the better artist.

Richard Lambert