Q. How do I find out what sort of poems The Rialto publishes? So I can select from my poems ones that they’ll like.

A. The answer to that used to be simply buy the magazine and read it. However recent issues (96, 98, 100) have been guest edited (by Degna Stone, Edward Doegar, and Will Harris + Ella Frears). Of course Michael Mackmin has approved the issues, so that’ll give a general indication. Maybe get hold of one of the ones he’s done? At least check who is editing the one you’re submitting to. Info on the website…

Q. What about their anthology Poetry With An Axe To Grind, will that help me to know what to send in?

A. Definitely. Will help you to know what kind of stuff goes on in his head. But it could be daunting as the choice is made from ninety-nine issues and includes some stellar poems/poets. They do publish all sorts of kinds of poetry.

Q. Does Michael ever say what he’s looking for?

A.You mean beyond saying things like ‘Just send us your best poems?’ He has said that he thinks poetry is the ‘most important art form we have’: but he often follows that up by saying maybe dance is more important.

Q. Can you be a bit more specific?

A. He does write about individual poems, on the website and in the Online Newsletter. You could do some research. For example there’s a piece called ‘Close Reading’ currently on the front page of the website. You might be able to unpick something of what he looks out for…

Q. Is it very technical?

A. I don’t think you need worry about that, I don’t think Michael knows the difference between a dactyl and an anapaest. He goes by some kind of inner clock which tells him if a poem ‘works’ or not. He’s usually careful to add ‘works for me’.

Q. I’m still not sure what kind of poems to send.

A. What do we know about Michael’s likes and dislikes? Well he has been known to say he doesn’t like poetry that ‘tries too hard’. And he does make a division in poems between ‘what the poem says’ and ‘how the poem says it’ (as in ‘I was interested in what you are writing about but less sure about how you write about it’). A symptom of ‘trying too hard’ is an over reliance on alliteration and referencing ancient poets – though the first poem in PWAATG, which he must like as he’s put it at the start of the anthology, has alliteration in its first two stanzas and a reference to Caliban at the end. Another sign of ‘trying too hard’ is poetry that shoves everything the poet thinks the world needs to know into one poem. He likes the poems on pages 15 and 18 of Poetry With An Axe to Grind because, he says, they ‘say a lot without shouting about it’. He gets turned off by ‘lazy’ vocabulary, when poets don’t think ‘is this the very best word?’. He’d rather talk about ‘goose shit green’ than ‘viridian motes’. He’s not keen on poems about cats (though they appear in The Rialto), doesn’t understand the need for poems ‘after’ e.g., ‘After George Bernard Shaw’ or ‘After Henri Matisse’ (though they too appear in The Rialto). He and his co-editor John Wakeman used to talk about ‘Poetry which works in its own terms’, whatever that means. He and the poet Matt Howard talk about poems that ‘need to have been written’ (ditto). He doesn’t mind ‘difficult’ poems (remembering that WH Auden reminded the world of the early importance of riddles). He also thinks highly of ‘accessible’ poetry….

Q. Thank you. Are you a robot?

A. That’s not a question I can help you with.

The Rialto, 22 October 2023

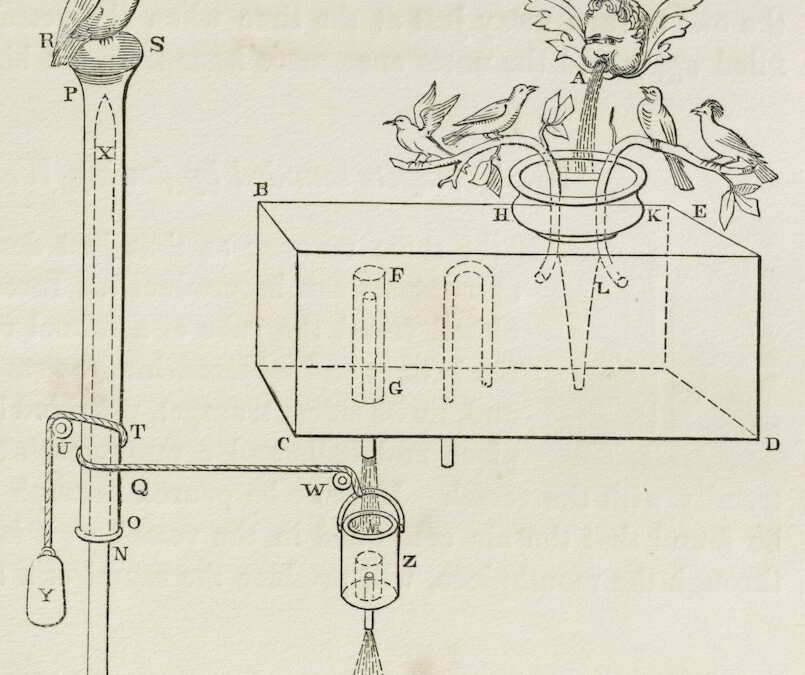

Image: Hero’s Pneumatica, Source Public Domain Review.