I have managed to give myself a very sharp attack of bloggers’ block. I came back to a grey Stansted on a comfortable and efficient Ryanair flight at the end of August firmly of the opinion that I’d quickly jot down a ‘what I did on my summer holiday’ blog. And now we have moved beyond November. True there’s a shiny new issue of the magazine out, so I’ve not been entirely idle, but I’ve still not sorted out my as-it-seemed-then important thoughts.

Usually I take the chance of holiday to scratch down a poem or three, or a few bits of poems – dragonflies that have managed to crawl up a stem since the last holiday and can now burst into winged glory. Nothing this time. I blame my own stubbornness. I was determined to finish a version of Apollinaire’s ‘La Jolie Rousse’ that I’d been tussling with for weeks. (Pretentious? Moi?). I’d found a copy of the 1959 Penguin Book of French Verse, one of that lovely series with the knocked back pastel covers, with abstract patterns on them, that I used to own in the days when I was a melancholic student. Think I re-bought it in Mr Ellis’ excellent bookshop on the corner of St Giles Street and Willow Lane in Norwich. Anyway this copy fell open, as second-hand books often do, at a previous owner’s favourite page. The poem is a war poem – Apollinaire was wounded in combat in 1916 and died in the ‘flu epidemic at the end of WW1. It hinges, for me, on the word ‘bonté’, which Penguin, in the essential (for me anyway) literal translation at the bottom of the page, render as ‘kindness’. ‘Kindness’ somewhat obsesses me at the moment. Anyway I’ve done a version of it that I’ll be sending shyly out to poetry magazines in the next few weeks.

A side-effect of reading the volume (more properly ‘flicking through’) was a little ‘ah-ha’ moment about the connection between modernist French poetry and the poetry from America that I read these days in that famous magazine Poetry, and which I suspect is an important influence on the younger poets that send work to The Rialto – particularly those selected by Nathan for issues 69, 70, and 71. In the ‘Introduction’ Anthony Hartley says ‘ A good deal of the obscurity of modern French poetry lies in the ceaseless succession of images often only connected by an arbitrary act of the poet’s will.’ Given the American writers’ love affair with France, pre (and post) ‘cheese eating surrender monkeys’, it suddenly made sense to me that, for example, Lowell’s ‘The Quaker Graveyard In Nantucket’, though possibly nudged into life by TS Eliot’s ‘drowned Phoenician sailor’, has got to owe a lot to Paul Valéry’s ‘Le Cimitiere Marin’, even if only in tone and rhythm.

And the block? The last time I did an after the summer holiday task, that I remember, was when I shifted to secondary school, and the first Art lesson of the autumn term. We hadn’t exactly done Art at Coombe Hill House. The oddly named Mr Spackman had come in once a week on a Thursday afternoon and given alternating lessons. One week he’d mark up a ‘pattern’ on the blackboard, a geometric affair which we copied using rulers etc., and then coloured in with our Lakeland pencils. The next week there’d be an arrangement of small cubes, or cylinders, that we had to draw freehand. That was it. But now a part of the kit for school was a set of pots of poster paints, Burnt Sienna, Chrome Yellow, Ultramarine Blue, Black, White, together with several long handled hog hair brushes. The teacher, immediately scary because he tried to overcome a wicked stammer by shouting, wrote titles on the board, gave out large sheets of sugar paper and bid us get on. I painted Dungeness Lighthouse. Romney Marsh was a place I exulted in and I loved the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Railway – a narrow gauge track that still runs the 13 miles between Hythe and Dungeness with a series of very beautiful one third size steam locomotives, built in the 1920s and 30s. That summer we went on the train from St Mary’s Bay, where we stayed most years in a rented chalet with Deco sunburst stained glass windows, all the way to Dungeness AND we went up the lighthouse – an expensive day out. It was hard to fit the lighthouse on the paper; it’s a tall column, set on a mound, with a bulbous top where the light lives.

As I was what was called in the 1950s a ‘late developer’ I hadn’t a clue why what I was sketching out, preparatory to colouring it in with my new paints, was causing giggles and glances from those near me. Some boys even found excuses to move around the room to take a look. Eventually I had the teacher standing beside me asking ‘W – W –W– W– WHAT’S THIS THEN?

He accepted what I said – even put the picture on the wall when it was finished, with a bright ultramarine sky and a black and white striped lighthouse. But the experience has led me to reflect on just how much the physical paralysis of shame has got to do with the development of depression.

I came to love this teacher. He encouraged me (though I couldn’t see why) to paint. He wangled me a ‘special prize’ for my oil painting in the competition to celebrate the return of H.M. The Queen on the Royal Yacht Britannia, after her post-coronation tour. The whole Junior School had been bussed out to some far North Kent Thames embankment to see this cool boat come motoring home. David B and I, embryo birders at that point, managed to find a whitethroat’s nest by falling over in a bed of nettles.

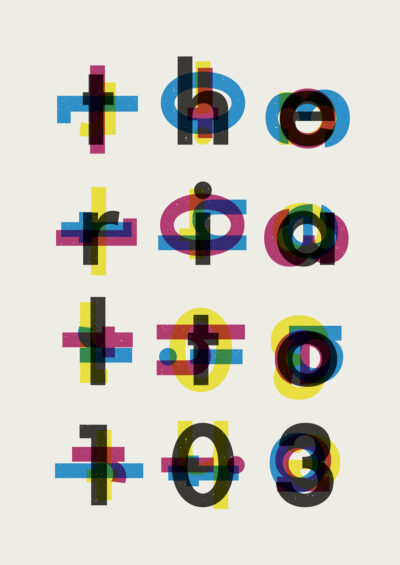

I became one of the very few children to ‘do’ O Level Art. I’m not sure about this, but I think that at the end of the last paper – the task was Still Life Drawing and he’d put a punnet of strawberries next to a bottle of wine – he shared out the fruit and poured the 3 or 4 of us a glass each. Not at all like the school I’d come to loathe. It seems an unlikely memory. But I did drink wine at least once in the Art Room: maybe, more likely, after I’d announced that I was giving up the idea of a career as an architect. Three of us had had this neat conspiracy going, we got Monday afternoons off school and went up by train and tube to the V & A where we’d draw furniture and stonework, and then, under the censorious hands of the ‘part-time’ Mr Dawson, transform our sketches with pen and brush (S– S–S–Sable) and lovely sepia ink into the beginnings of a portfolio. The other thing about the Art Room was that it had, behind a screen, a working Letterpress.

So what about Keats then? Mr Etherington read us Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ and I discovered that I had hairs on the back of my neck. There was a second-hand bookshop in South Croydon. As both my parent’s were at work and not home until after 6 in the evenings (partly to pay for the expensive education that they thought I needed), I quite often didn’t hurry home – particularly once practice for the school rugby and hockey teams had given up on me, sometime during the crisis of puberty. I bought myself Palgrave’s Golden Treasury. I later discovered that this was a mistake, full of what was uncool kitsch poetry, but I loved it and read it under the bed-clothes late at night. I’m sure ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci'(Reader, I married her) was in it. It was poetry in the realm of such lines as ‘Peace ho! the moon sleeps with Endymion and would not be waked’, the sheer emotional blast of which can still fill me with tears.

Later on, swimming against the stream, I found Keats’ ‘Odes’. I can recall reading both the Ascent of F6 and The Dog Beneath The Skin (the Auden/Isherwood collaborations) aloud in class. I think we were supposed to be more interested in politics than in sex. I can’t remember being encouraged to read Keats – Coleridge, a notorious drug addict, was considered thoroughly OK but he and Wordsworth had been political utopians, at least in their youth. However, I discovered that there were nightingales in the woods near Farleigh: I didn’t quite go as far as to read the ode at them (though I might now) but the song does fit amazingly to the poem. You can make the experiment by reading the poem and listening to the various YouTube recordings at the same time.

I was reading Keats partly because I’d gathered that he was a poet that girls liked, and partly because I thought he’d help me to find out about sex. I plunged into ‘The Eve Of St Agnes’ with growing arousal because I thought it might actually describe IT happening – the copy of The Decameron that I’d got from the second-hand bookshop did, but reverted to the Italian at the key point. All Keats told me was that sex involved a lot of fruit and junket and ‘sirop’ and general baked meats, but the poet turned out to be virginal because all that happens after a lot of (well sustained) narrative stanzas is that he and the girl run away into the stormy night. Some lovely bits – like the way the wind lifts the carpets off the castle floors.

At the time (Late 1950s) it was believed that poets were the last people that should be allowed to read their work aloud. This was the age of Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, and John Gielgud – you can Google Gielgud’s Hamlet soliloquys if you want to get a flavour of ‘poetry’ as it then sounded. Avid enthusiast for The Third Programme that I was (how often do you get Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy broadcast these days?), I was all in favour of this magniloquent voice style. I did, by the bye, in the sixth form, play Polonius to Martin Jarvis’ Hamlet…. Anyway Keats is perfect for actorly reading. First there’s the general air of melancholy – ‘I have been half in love with easeful death,’ understandable when you consider that if you had TB in the C19 you knew death intimately, second there’s the general longing for, and terror of, consummation, the key text here is the ‘Ode On a Grecian Urn,’ and thirdly there is the verse itself. In ‘To Autumn,’ for example, there’s lots of alliteration, internal rhyming, long vowels and double consonants –

‘And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd and plump the hazel shells’.

Look at all the ‘l’s, consider the impossibility of reading it quickly, the words continually slow you, ‘ripeness’, ‘core’, ‘gourd’ just have to be lingered over: and ‘plump’ is lovely. Or consider the last lines of the first two stanzas

‘For summer has o’erbrimmed their clammy cells.’ And

‘Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.’

The double ‘m’s in the first, the long vowels in the second, slow time down (never mind the loaded sensuousness of what the words actually say).

I’ve enjoyed reading the poems again. The bloggers block? Hope I’ve moved on from it.

Michael Mackmin