A WITNESS by Amy Carrington

I’ve been watching the letterbox, I’ve been watching her

at the letterbox. Her arm is stuck in the rectangle,

but not stuck getting out

she can’t seem to get it any farther in.

A gloss-eyed pot fox peers through the doily curtain with me,

the net glued by condensation to the café window.

There are rows two deep of bric-a-brac, dotted

worn and spotted along the sill.

The syrupy tea swill left in my mug is sandy, and cold –

and I layer up to go for a smoke.

She is on her toes, face scrunched like a tragedy mask.

I stay on my side of the street, and watch.

A guy stops. ‘That’s illegal you know.’ She looks at him

like he is mad. ‘It doesn’t belong to you once it’s in there.’

‘I haven’t let go yet.’

The guy shakes his head and walks on.

She watches him leave, it turns her body,

her arm moves just an inch out

of the letterbox and I see the second the letter drops,

flicks out of her hand and into the white stacks. Gone.

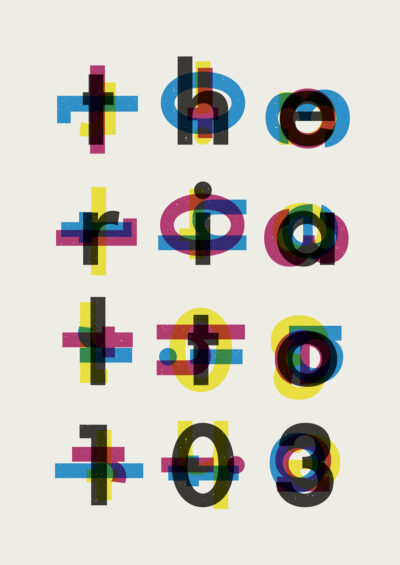

I’m curious about my decision to choose to write about this poem from the new issue of The Rialto (86). There are many important and poignant poems that I could have selected – Karen McCarthy Woolf’s ‘Outside’, for example, or Liz Berry’s ‘Foal’, Anita Pati’s ‘Silver Jubilee’, David Morley’s ‘Own’, or the chilling Steph Morris poem ‘What to Take on Flight’. Amy’s ‘A Witness’ is a poem about being stuck, it’s a poem about the severe difficulties that some people have with commitment and decision. It’s also a poem with some delightfully accurate observation. The café’s a more 1950s or 1960s independent café than today’s chain clones. Maybe South Croydon and me lingering on the way home from school? I like the ‘pot fox’ and other unwashed ornaments along the sill, I like the curtains ‘glued by condensation’. Though it actually has to be a poem of today because the narrator has to ‘layer up to go for a smoke’. I like the believable exchange between the passer-by (typical Critical Parent in Transactional Analysis terms) and the person struggling to post the letter. I love the ‘white stacks’, the huge potential of unopened mail. And I also rather particularly like the fact that the narrator observes, notes the phenomena, and commentates on what is seen without speculating, for example, on the contents of the letter. Being engaged and disengaged, empathic, but not seeking (beyond being present in the field) to influence the outcome. The only clue we get is ‘tragedy mask’, but that can just be an ironic observation. What’s also good is the ending (the poem has clear and concise beginning and ending stanzas, if you are taking notes on how to write), the way that the slight movement, the ‘just an inch’, is enough to resolve the drama. As with all procrastination and stuckness, movement, any kind of movement, can produce change – I’m shy to tell you how many times just writing this paragraph I’ve had to get up and wander downstairs to the kitchen on non-existent errands before I can get the next sentence started. So, I have a personal contact with the action in the poem and that’s partly why I like it: nevertheless the poem is excellent because of its psychological accuracy, because of its direct and accessible language (there’s no attempt to poeticize what’s going on), because it tells a story clearly, because the observations are exact and described exactly, because it has a very neat title, and so on… I also like the tongue in cheek assertion that the letter itself takes a hand in the process, it, ‘flicks out of her hand’.

Michael Mackmin

You can buy issue 86 here.